Under current law, the home mortgage interest deduction (HMID) allows homeowners who itemize their tax returns to deduct mortgage interest paid on up to $750,000 worth of principal, on either their first or second residence. The current $750,000 limitation was introduced as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and will revert to the old limitation of $1 million after 2025.

The benefits of the HMID go primarily to high-income taxpayers because high-income taxpayers tend to itemize more often, and the value of the HMID increases with the price of a home. While the total value of the HMID went down due to the TCJA, the share of benefits is now more concentrated among high-income taxpayers due to more taxpayers opting for the more generous standard deduction.

Though the HMID is often viewed as a policy that increases the incidence of homeownership, research suggests the HMID does not accomplish this goal. There is, however, evidence that the HMID increases housing costs by increasing demand for housing among itemizing taxpayers.

Although the home mortgage interest deduction is in need of reform, there is a tax policy justification for it. Since lenders pay taxes on the mortgage interest they receive, deductibility of mortgage interest is the appropriate treatment of interest for homeowners who finance with debt. More generally, the tax code treats housing more neutrally than how it treats investment in other assets. Though owner-occupied housing is the beneficiary of several prominent tax expenditures, these tax expenditures mean that the treatment of owner-occupied housing is more consistent with how it would be treated in a consumption tax.

The TCJA reduced the amount of principal available for the HMID from $1 million to $750,000. This increased the tax burden on owner-occupied housing, particularly for debt-financed homes. These limitations bias the tax code toward equity-financed homeownership and increase the tax burden on owner-occupied housing overall.

The HMID can be reformed in several ways. Policymakers could make the deduction more efficient by narrowing the difference in effective marginal tax rates between owner-occupied housing and other forms of capital. To address distributional concerns, policymakers could make the deduction more available to low-income taxpayers by making the deduction a tax credit A tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. . Additionally, making the credit a fixed amount, instead of a percentage of a homeowner’s mortgage, could keep the tax code from encouraging the purchase of larger homes.

The Revenue Act of 1913 made all forms of personal and business loan interest deductible. At the time, many businesses were family-run, and the government could not distinguish between personal and business-generated interest.[1] For much of the twentieth century all consumer loan interest was deductible. This policy became expensive, especially during the 1970s’ credit card boom.[2] As a result, the personal interest deduction provisions were scrutinized in the 1980s.[3]

The Reagan Administration did not significantly limit the HMID as it broadened the tax base The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. to raise revenue for the Tax Reform Act of 1986.[4] Though that Act introduced a $1 million cap on eligible principal, mortgage interest remained largely deductible for itemizing homeowners.[5] Following the financial crisis of 2008, policymakers began to question whether the HMID should be allowed to reduce costs for homeowners if it subsidizes riskier loans. This shift made changes to the HMID viable for 2017 tax reform.[6]

Under current law, individuals who itemize can deduct interest paid on their mortgage up to $750,000 in principal from their taxable income Taxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . This cap on mortgage principal was reduced from $1 million as part of the individual income tax An individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. changes in the TCJA. The current $750,000 cap applies through 2025, after which the cap will revert to the pre-TCJA level.[7]

If mortgage principal exceeds $750,000, taxpayers can deduct a percentage of total interest paid. For example, a taxpayer with mortgage principal of $1.5 million on a single home acquired in 2018 would be able to deduct 50 percent of their interest payments over the life of their mortgage ($750,000/$1.5 million). The cap applies to both primary and secondary residences.[8] If a person purchases two homes at $500,000 each (totaling $1 million) the interest on the principal of the first house would be fully deductible, and interest on $250,000 in principal on the second would be deductible at a reduced rate.[9]

The TCJA also changed rules for interest deductibility on home equity loans. Prior to the TCJA, interest on up to $100,000 of home equity loans was deductible in addition to interest paid on up to $1 million in principal. This loan could be used for expenses like credit card debt or tuition. After the TCJA, home equity loans are now included within the mortgage’s principal, and interest is only deductible if used to build or improve a qualifying residence.[10]

The U.S. Treasury Department estimates that the HMID will reduce federal revenue by $597.6 billion from 2019-2028. The tax expenditure Tax expenditures are a departure from the “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses, through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. Expenditures can result in significant revenue losses to the government and include provisions such as the earned income tax credit (EITC), child tax credit (CTC), deduction for employer health-care contributions, and tax-advantaged savings plans. is smaller relative to the pre-TCJA baseline because of the lower cap for mortgage principal from 2019 through 2025, the fewer itemizers, and lower statutory tax rates. As such, the revenue impact of the HMID will grow after 2025 because the TCJA’s individual income tax provisions will expire. [11]

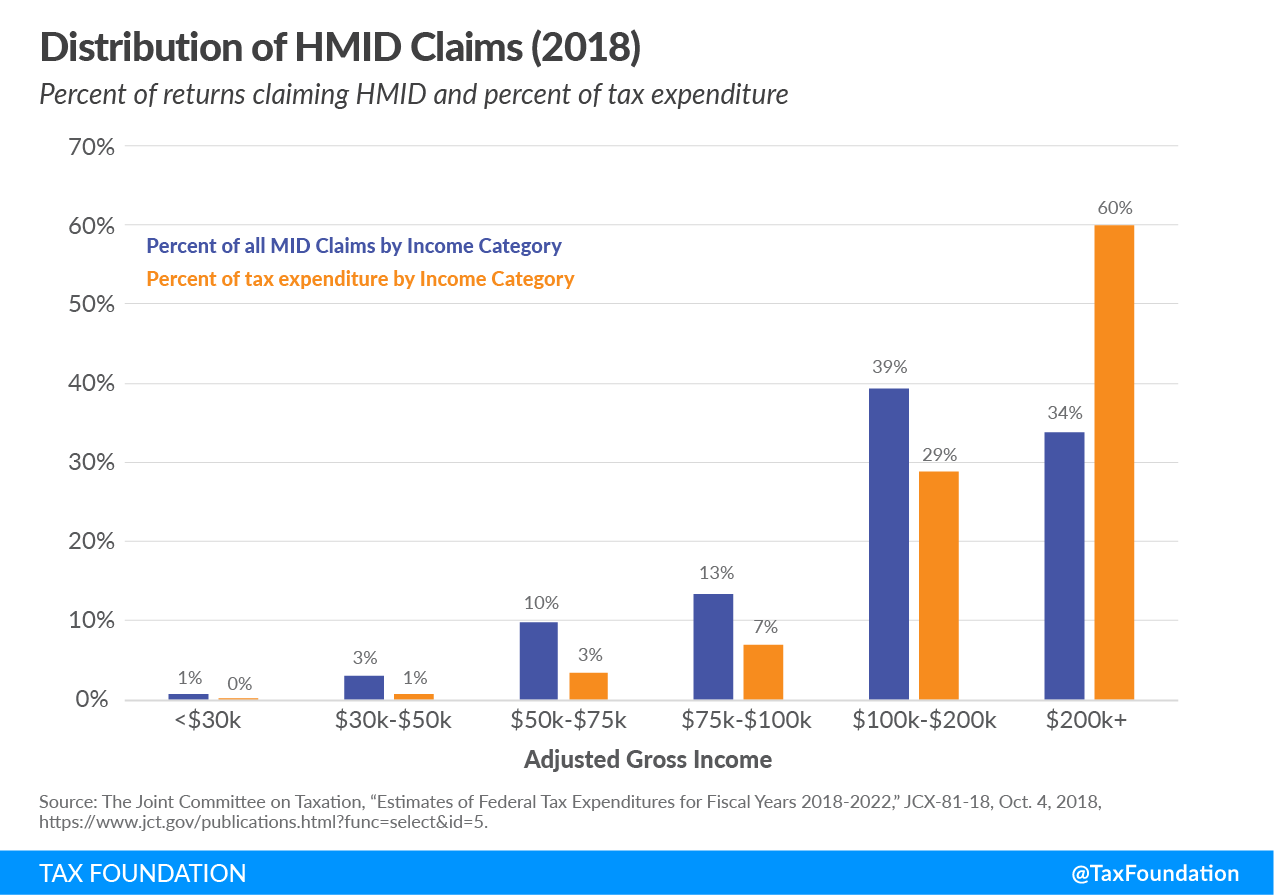

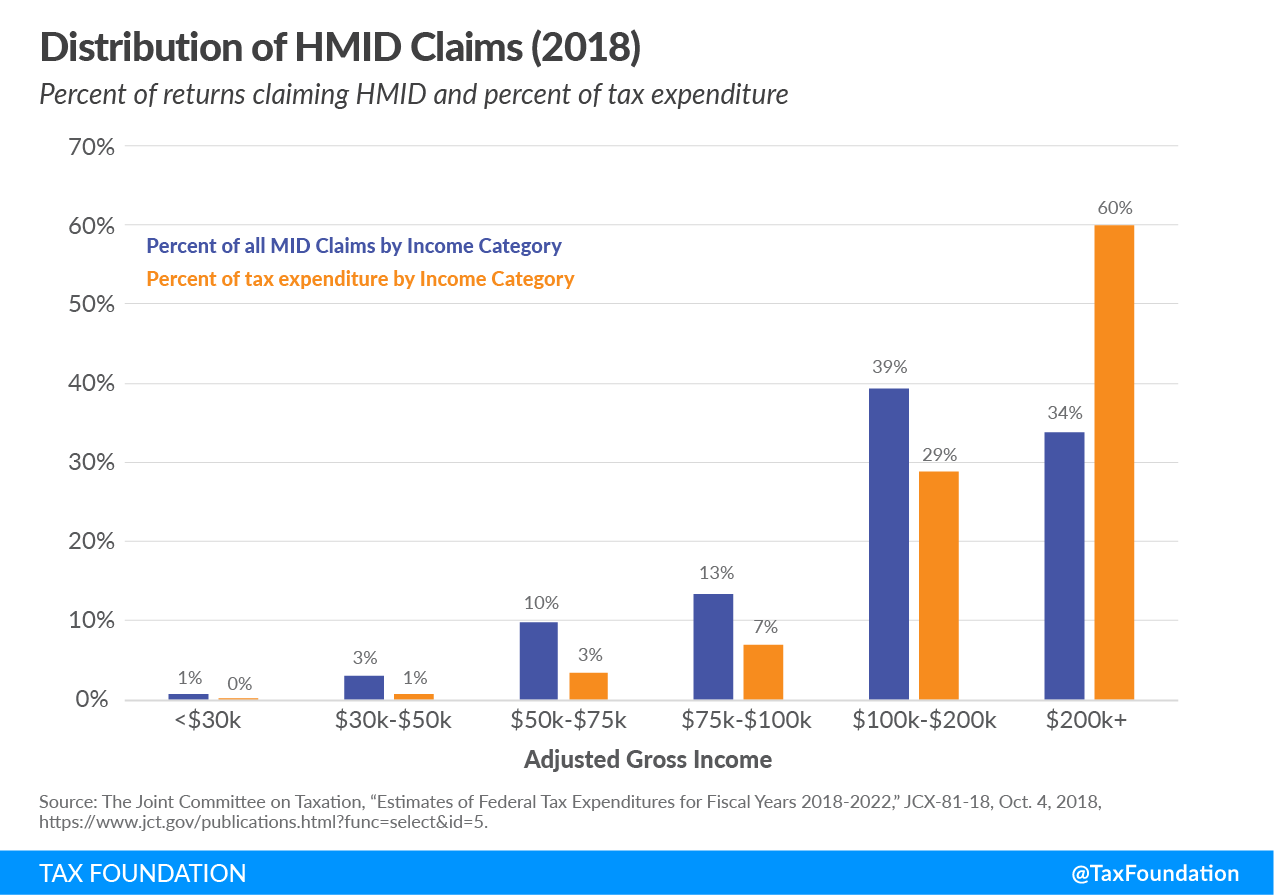

The home mortgage interest deduction reduces tax liabilities most for high-income taxpayers. Figure 2 shows the proportion of returns claiming the HMID and the amount of the total tax expenditure taken by income group. Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates show that both the proportion of taxpayers that will claim the HMID and the amount of the tax expenditure taken will increase with income in 2018. Less than 4 percent of taxpayers earning less than $50,000 will claim the HMID, and these taxpayers will take less than 1 percent of the total tax expenditure. Taxpayers earning over $200,000 will make up 34 percent of HMID claims and will take 60 percent of the total tax expenditure.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

There are several reasons why high-income taxpayers receive most of the forgone revenue from the HMID. To claim the HMID, a taxpayer must itemize their return. Under current law, the share of taxpayers itemizing their deductions in 2019 will be about 13.7 percent. This proportion is significantly lower than what the proportion would have been in 2019 under pre-TCJA law, which would have been just over 31 percent. This is because the TCJA expanded the standard deduction The standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. from $6,500 in 2017 to $12,000 in 2018 ($13,000 to $24,000 for married filing jointly). Now, fewer taxpayers itemize overall, and the proportion of taxpayers itemizing increases with income. [12]

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, April 2019.

Higher income taxpayers itemize more often and are more likely to benefit from the home mortgage interest deduction because their total expenses are more likely to exceed the value of the standard deduction. [13] For instance, a homeowner that just secured a $200,000 mortgage at a 5 percent interest rate would receive roughly $10,000 in interest deductions over the first year; a 5 percent interest rate on a $750,000 mortgage would be worth about $37,500.[14]

Additionally, deductions tend to benefit high-income taxpayers more than low-income taxpayers because of our progressive income tax. A person in the bottom tax bracket reduces their tax liability by 10 cents for each dollar they deduct, while a person in the top tax bracket reduces their tax liability by 37 cents for each dollar they deduct on income within that tax bracket. [15]

HMID proponents argue the deduction encourages homeownership by reducing the cost of debt-financed homeownership.[16] Yet, research suggests the HMID does not increase homeownership rates.[17] There is also no relationship between homeownership rates and the proportion of the population that itemizes, suggesting taxpayers do not rely on the HMID to afford a home.[18]

Research does suggest that the home mortgage interest deduction increases housing costs by increasing demand for housing, [19] which limits the policy’s ability to increase homeownership.[20] As such, eliminating the deduction could increase housing costs for some itemizing taxpayers, but reduce overall demand and lower prices and make owner-occupied housing available to a broader group of people.[21]

The HMID may also makes housing prices more volatile. Since home mortgage interest deductions are capitalized into home costs, U.S. home prices are higher than they otherwise would be, and higher housing prices discourage people from moving.[22] This means housing market changes are not consistently incorporated into the price of individual houses, leading to more price volatility.[23] This volatility could be problematic because uncertainty about prices has a negative impact on homeownership, perhaps more than any particular housing policy. [24]

Others argue housing-related tax policies might have contributed to the 2008 financial crisis by encouraging people to buy homes they could not afford.[25] The HMID is more valuable to risky borrowers in the U.S. because the deduction’s cap is based on a loan’s principal, not on the amount of interest deducted. This allows riskier homebuyers with higher interest rates to benefit more than less risky homebuyers. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether tax factors were more important relative to other factors—such as other public policies aimed at expanding homeownership. Housing prices also went up in other countries with much different tax systems than in the U.S., pointing to other factors.[26]

The discussion of the HMID is typically in the context of whether it encourages homeownership. As discussed above, research suggests that it fails to encourage homeownership. However, the home mortgage interest deduction does represent sensible tax policy. Overall, owner-occupied housing, as a capital asset, is treated somewhat correctly. However, this treatment is favorable relative to other types of investment.

Housing, like any other capital investment, provides a return to the individual or business that owns the asset. For a business, housing provides a return through the rent that a tenant pays. The return is the same for an individual that happens to live in their own home, but the rent is effectively paid to themselves. This return to individuals is called “imputed rental income.”

Under current law, the returns to owner-occupied housing are not taxed, for the most part. Individuals do not need to report or pay tax on imputed rental income. Taxpayers can also exclude $250,000 in capital gains ($500,000 for married taxpayers) on the sale of an owner-occupied home from their taxable income if they have lived in the home for two of the previous five years. [27] This tax treatment of owner-occupied housing is analogous to how Roth IRAs treat retirement saving.[28]

For homeowners that finance the purchase of a house with a mortgage, interest paid to a lender is deductible while the interest received by the lender is taxable. In principle, this treatment of interest is neutral as all deductible interest paid should match up with taxable interest received. In practice, however, some interest payments may be deductible by the borrower and taxed at a lower rate or not at all for a lender. Or, not deductible for a borrower and taxable for a lender.[29] This results in either a net subsidy or tax on borrowing.

The impact the income tax has on housing can be summarized by measuring the effective marginal tax rate The marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. (EMTR) on housing. An EMTR is a summary measure, expressed as a single percentage, that estimates how a tax system reduces the return to, and thus the incentive to invest in, a new asset, like a house.

An EMTR can be thought of as a tax “wedge” equal to an investment’s pretax rate of return minus its after-tax rate of return, divided by its pretax rate of return. For instance, if a tax takes 3 percentage points of a 9 percent pretax rate of return, the EMTR on the asset would be 33.3 percent ((.09-.06)/.09). Assuming that the investment needed a 6 percent after-tax return in order to break even and satisfy investors, the investment’s rate of return needed to increase by 50 percent to cover the tax.[30]

An EMTR of zero means that taxes do not impact marginal investment decisions, while a positive (negative) EMTR means the tax code discourages (subsidizes) a marginal investment. Large differences in EMTRs among assets is a sign of economic inefficiency, because the tax code encourages investment in capital with lower EMTRs compared to capital with higher EMTRs.[31]

Under current law, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the EMTR on owner-occupied housing will be positive between 2018 and 2025, ranging from 5.1 percent to 6.8 percent. Equity-financed housing receives near-neutral treatment with an EMTR of -0.4 percent until 2025. In contrast, debt-financed housing faces a positive tax burden—ranging from 17.8 percent to 22.5 percent.

In 2026, the EMTR on housing will fall below zero, to around -3 percent. This is due to the expiration of the individual income tax changes passed as part of the TCJA. The TCJA’s expansion of the standard deduction limited the number of itemizers who will deduct home mortgage interest. And for those that itemize, the value of the mortgage interest declined because of the reduction in allowable principal from $1 million to $750,000. These changes will expire in 2025.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data,” Tax Parameters and Effective Marginal Tax Rates, EMTR on Capital, Apr. 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data.

The TCJA’s limitations on mortgage interest deductibility made owner-occupied housing a less attractive investment option by making it more expensive. However, it narrowed the gap in tax burden between owner-occupied housing and other forms of capital. This gap could contribute to overinvestment of owner-occupied housing relative to other investments.[32] However, owner-occupied housing is attractive compared to other assets because it roughly receives proper tax treatment while other forms don’t.[33] For context, the EMTR on all capital assets (including owner-occupied housing) will range from 14.5 percent to 16.5 percent between 2018 and 2028, while the EMTR on all businesses (including C corporations and pass-through entities, excluding owner-occupied housing) will range from 18.4 percent to 24.4 percent.[34]

Policymakers could reform the HMID in several ways. Policymakers could turn the HMID into a tax credit to make the policy more available to low-income taxpayers. Policymakers could also make this credit a flat amount that would not vary based on the value of a taxpayer’s home, which would keep the policy from encouraging the purchase of larger homes than one can afford . Policymakers could also reduce the difference in EMTRs between owner-occupied housing and other assets which would reduce distortions in the tax code, but doing so would require major changes to the tax code.

One way to increase benefits for lower-income households would be to make the deduction a tax credit. Taxpayers would not have to itemize to receive a tax credit. Research has also found replacing the HMID with a credit that reduces federal revenue by the same amount would better target homeownership subsidies to lower-income taxpayers, with refundable tax credits providing the most benefits to the bottom quintile of taxpayers.[35]

Requiring that any credit for homeownership be a fixed amount of money—as opposed to a percentage of one’s mortgage payments—would also keep the tax code from encouraging the purchase of bigger homes than one can afford. For instance, Fichtner and Feldman recommend a fixed $900 credit for anyone with a mortgage, granted over a number of years. Such a credit would increase homeownership rates, but because the credit is fixed, the value of the credit would not increase with a taxpayer’s home value.[36]

Policymakers could also reduce distortions among different types of capital investments by reducing the tax burden on other types of capital assets. For example, the CBO has laid out three sequential steps that could transition the U.S. tax code away from taxing capital income. The first would be to remove various restrictions placed on individual retirement accounts, which would lower effective tax rates on capital income at the individual level. The second would be to allow full expensing Full expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of capital acquisitions, which would lower effective rates for businesses. The third step would be to disallow net interest deductions. All these reforms would ultimately set EMTRs on all capital investment, including housing, to zero. [37]

Eliminating the HMID could also reduce the difference in EMTRs among capital assets. However, this would raise the effective tax rate on housing, unless you also got rid of taxation on interest received—this could be accomplished with a broad reform to how interest is treated.[38]

While many consider the home mortgage interest deduction to be a policy that increases the incidence of homeownership, research suggests the deduction does not increase homeownership rates. In contrast, the deduction increases home prices by making homeownership more affordable for itemizing taxpayers, which could limit the deduction’s ability to impact homeownership. Data support the idea that the deduction benefits wealthier taxpayers more than lower-income taxpayers, largely because the deduction requires a person to itemize, and the deduction’s benefits increase with the price of a home.

Yet, the home mortgage interest deduction does represent reasonable tax policy. The deduction is part of a broader set of policies that treat saving in owner-occupied housing neutrally with the decision to consume. Because the HMID is viewed by some as a subsidy for homeownership, owner-occupied housing is attractive relative to other forms of saving because other forms of capital investment are treated poorly under our tax code. The TCJA’s limitations on the home mortgage interest deduction and larger standard deduction increased the tax burden on owner-occupied housing.

Policymakers could improve economic efficiency by making the tax burden on owner-occupied housing closer to the tax burden placed on other capital assets, either by eliminating the deduction or by removing capital from the tax base. For those with distributional concerns, the HMID could be converted into a tax credit based on a fixed dollar amount. This would make the policy more available to homeowners at all income levels, as taxpayers would not have to itemize to claim the credit. This policy would also mean the value of the HMID would not depend upon the size of a homeowner’s mortgage.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Dennis J. Ventry Jr., “The Accidental Deduction: A History and Critique of the Tax Subsidy for Mortgage Interest,” Law & Contemporary Problems 73 (Mar. 18, 2011), 102-166, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1498784.

[3] Ventry Jr., “The Accidental Deduction: A History and Critique of the Tax Subsidy for Mortgage Interest.”

[7] Mortgages established prior to December 15, 2017 still qualify for interest deduction on the last $250,000 of principal. Any refinance-related mortgage debt is associated with the original date of the mortgage. (If it was refinanced before December 15, 2017, the applicable cap is still $1 million; if not, it is $750,000.) Any new loan cannot surpass the cost of the original loan. See U.S. Code 26 § 163(h)(3)(F). See also Congressional Research Service, “2018 Tax Filing Season: The Mortgage Interest Deduction,” Jan. 8, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11063.pdf.

[8] Taxpayers cannot deduct home mortgage interest from more than two homes, and the second home must be used by the taxpayer as a residence. Qualified residence means “the principle residence…of the taxpayer, and…1 other residence of the taxpayer which is selected by the taxpayer…(and) used by the taxpayer as a residence.” See U.S. Code 26 § 163(h)(4).

[9] Congressional Research Service, “2018 Tax Filing Season: The Mortgage Interest Deduction.”

[10] See particularly U.S. Code 26 § 163(h)(3)(F)(i)(I), Congressional Research Service, “2018 Tax Filing Season: The Mortgage Interest Deduction,” and Congressional Research Service, “2019 Tax Filing Season (2018 Tax Year): Examples of Deducting Interest on Mortgage Debt and Home Equity Loans,” Feb. 21, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11111.pdf.

[11] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, “Tax Expenditures,” October 19, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Tax-Expenditures-FY2020.pdf. JCT estimates that the HMID will cost $163.2 billion from 2018-2022. See The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?id=5148&func=startdown.

[13] Scott Greenberg, “Who Itemizes Deductions?” Tax Foundation, Feb. 22, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/who-itemizes-deductions/.

[14] The mortgage interest deduction declines in value as a homeowner pays off mortgage principal, making the deduction more valuable in the early years of the mortgage. See Maurie Backman, “How Do I Calculate My Mortgage Interest Deduction,” The Motley Fool, Mar. 11, 2017, https://www.fool.com/retirement/2017/03/11/how-do-i-calculate-my-mortgage-interest-deduction.aspx.

[15] Anna Tyger and Scott Eastman, “The Regressivity of Deductions,” Tax Foundation, June 28, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/regressivity-of-deductions/.

[16] National Association of Realtors, “Mortgage Interest Deduction,” https://www.nar.realtor/mortgage-interest-deduction, and Ventry Jr.’s discussion in, “The Accidental Deduction: A History and Critique of the Tax Subsidy for Mortgage Interest.”

[17] William G. Gale, Jonathan Gruber, and Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, “Encouraging Homeownership Through the Tax Code,” Tax Notes, June 18, 2007, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/encouraging-homeownership-through-tax-code/full, and Edward L. Glaeser and Jesse M. Shapiro, “The Benefits of the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction,” NBER Working Paper No. w9284, Oct. 19, 2002, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=342440.

[18] Glaeser and Shapiro, “The Benefits of the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction,” and Lowenstein, “Who Needs the Mortgage-Interest Deduction?”

[19] Dan Andrews, “Real House Prices in OECD Countries: The Role of Demand Shocks and Structural and Policy Factors,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 831, Dec. 13, 2010, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5km33bqzhbzr-en.pdf?expires=1561745202&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=E62281A3DEF80FC7178B347B097884A1.

[20] Steven C. Bourassa, Donald R. Haurin, Patric H. Hendershott, and Martin Hoesli, “Mortgage Interest Deductions and Homeownership: An International Survey,” Swiss Finance Institute, Research Paper Series N12-06, Mar. 13, 2013, https://www.nmhc.org/uploadedFiles/Articles/External_Resources/SSRN-id2002865.pdf.

[21] Kamila Sommer and Paul Sullivan, “Implications of US Tax Policy for House Prices, Rents, and Homeownership,” American Economic Review 108(02): 241-274, February 2018, /wp-content/uploads/2019/04/An-Overview-of-Capital-Gains-Taxes.pdf.

[22] Tamim Bayoumi and Jelle Barkema, “Stranded! How Rising Inequality Suppressed US Migration and Hurt Those Left Behind,” International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Paper No. 19/122, June 27, 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3411031.

[23] Andrews, “Real House Prices in OECD Countries: The Role of Demand Shocks and Structural and Policy Factors.”

[24] Harvey S. Rosen, Kenneth T. Rosen, and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, “Housing Tenure, Uncertainty, and Taxation,” NBER Working Paper Series No. 1168, July 1983, https://www.nber.org/papers/w1168.pdf.

[25] Rebecca N. Morrow, “Billions of Tax Dollars Spent Inflating the Housing Bubble: How and Why the Mortgage Interest Deduction Failed,” Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law 17:3 (2012), https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1308&context=jcfl.

[26] Vieri Ceriani, Stefano Manestra, Giacomo Ricotti, Alessandra Sanelli, and Ernesto Zangari, “The tax system and the financial crisis,” PSL Quarterly Review 64:256 (2011), 39-94, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f541/59644c622730a9dee283c9d8512ff2e36220.pdf.

[27] Additionally, taxpayers can only take this capital gains exclusion once every two years. See Erica York, “An Overview of Capital Gains Taxes,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 16, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/capital-gains-taxes/.

[28] Congressional Budget Office, “Taxing Capital Income: Effective Rates and Approaches to Reform,” October 2005, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/109th-congress-2005-2006/reports/10-18-tax.pdf.

[29] Alan Cole, “Interest Deductibility – Issues and Reforms,” Tax Foundation, May 4, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/interest-deductibility/.

[30] A marginal investment is a “break-even” investment that would provide a return just large enough to satisfy investors after tax. Projects with a return lower than this break-even investment would not be pursued because they would not generate a profit sufficient to satisfy investors. See Congressional Budget Office, “Taxing Capital Income: Effective Rates and Approaches to Reform.”

[32] Erica York, “Three Points on the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 8, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/three-points-mortgage-interest-deduction/.

[33] Alan Cole, “A Partial Defense of the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 20, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/partial-defense-mortgage-interest-deduction/.

[34] Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data: Tax Parameters and Effective Marginal Tax Rates,” EMTR on Capital, April 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data.

[35] Eric Toder, Margery Austin Turner, Katherine Lim, and Liza Getsinger, “Reforming the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” Urban Institute and the Tax Policy Center, April 2010, http://urbaninstitute.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412099-Reforming-the-Mortgage-Interest-Deduction.PDF.

[36] Jason Fichtner and Jacob Feldman, “Reforming the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” The Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Working Paper No. 14-17, June 2014, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Fichtner-Reforming-Mortgage-.pdf.

[37] Congressional Budget Office, “Taxing Capital Income: Effective Rates and Approaches to Reform.”

[38] Cole, “Interest Deductibility- Issues and Reforms.”